Photo: Portland Appraisal Blog

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Understanding Measure 50: The Foundation of Tax Compression

- The Data: Tax Compression in the Portland Metro Market

- The Veteran and Active-Duty Exemptions

- The 2024 Rule Change

- Real-World Implications

- What Appraisers Should Do

- Closing Thoughts

Introduction

Imagine closing on a well-maintained pre-1940 Craftsman in an established close-in Portland neighborhood. The sale price felt fair, the taxes shown on the listing and county statement appeared reasonable, and the transaction cleared due diligence without issue. Then the next year’s tax bill arrives—$2,000 to $6,000 higher than anticipated. The increase isn’t due to a sudden spike in market value, but to a change in how Oregon counties now calculate Maximum Assessed Value (MAV) when certain partial property tax exemptions end.

This situation is no longer hypothetical. Oregon REALTORS first highlighted the risk in a December 12th, 2025 internal “Forms Tip of the Week” communication, alerting members that the loss of veteran or active-duty partial exemptions—commonly triggered when a qualifying veteran or surviving spouse sells the home or passes away without a qualifying successor—can lead to significant tax increases under updated guidance from the Oregon Department of Revenue.

While the veteran and active-duty exemptions (ORS 307.250 and 307.286) have drawn attention to the issue, the underlying driver is broader: the substantial tax compression created by Measure 50 for properties built or long-held before 1997.

Historically, when these modest partial exemptions ended, counties simply removed the discount and allowed the low underlying MAV to continue. The 2024 guidance change now enforces a constitutional requirement to reset MAV closer to current market reality upon disqualification.

The outcome: buyers may face permanently higher carrying costs they did not expect, sellers (including veterans and surviving spouses) can find their properties harder to market at full value, and appraisers encounter a marketability factor worthy of note when present.

This Deep Dive reviews the mechanics, illustrates the pattern with Portland Region sales data, and provides practical steps for identifying and addressing the issue in appraisal assignments.

Understanding Measure 50: The Foundation of Tax Compression

To grasp why the loss of a veteran or active-duty exemption can now lead to significant tax increases, we must first understand Oregon’s Measure 50 property tax system, approved by voters in 1997.

Measure 50 replaced the previous tax structure with two key values for each property:

- Real Market Value (RMV): The county assessor’s estimate of what the property would sell for on the open market. This value can rise or fall annually with market conditions.

- Maximum Assessed Value (MAV): A separate taxable value created by Measure 50. For existing properties in 1997, MAV was initially set at approximately 90% of the 1995–1997 RMV. Thereafter, MAV is generally limited to a 3% annual increase, with exceptions for major additions, improvements, or certain other events.

The Assessed Value (AV) is the lesser of RMV or MAV. Taxes are calculated by multiplying the AV by the local tax rate.

In high-appreciation markets like the Portland metro area, this 3% cap creates substantial tax compression over time. A home purchased or built before 1997 can have an MAV far below its current RMV after decades of strong market growth.

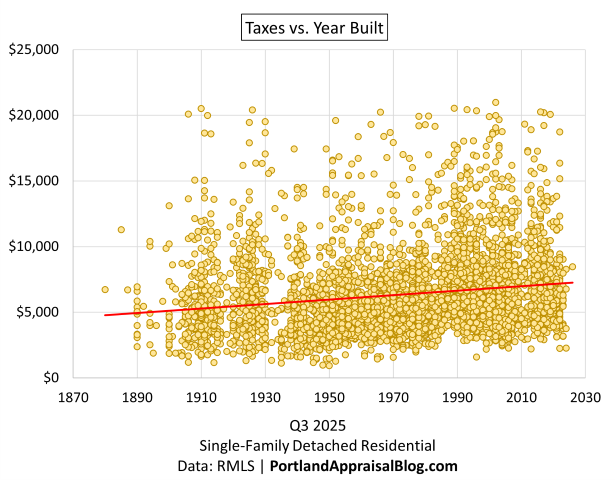

Note: Scatter plots are limited to properties with annual taxes of $21,000 or less to highlight the primary distribution and improve readability.

The scatter illustrates the effect clearly: pre-1960 homes are overwhelmingly clustered below $10,000–$12,000 in annual taxes, with the densest grouping under $8,000–$9,000. Properties on the far left (pre-1920 builds) often show the deepest compression, having benefited from the longest period of capped MAV growth. Post-1990 homes, by contrast, display significantly higher tax burdens, reflecting less historical compression.

When a triggering event occurs—such as disqualification from a partial exemption—the MAV can be recalculated using the Changed Property Ratio (CPR), typically around 0.54 for residential properties in Portland Region counties for the 2025–2026 tax year, applied to current RMV.

In the next section, we examine local sales data that quantifies the scale of this compression and illustrates why the reset can matter in real transactions.

The Data: Tax Compression in the Portland Metro Market

Q3 2025 sales data from detached single-family residences (SFR) in the Portland Region (Clackamas, Columbia, Hood River, Multnomah, Washington, and Yamhill counties) illustrates the scale of Measure 50 compression and why a MAV reset can create material differences in carrying costs.

The table below summarizes average sale prices and annual property taxes by approximate decade built. Flagged new construction is excluded due to frequently incomplete or preliminary tax assessments at the time of sale, which can distort the pattern of long-term compression. This brings the Q3 2025 dataset to 4,256 sales total.

| Decade Bucket | Avg Sale Price | Avg Annual Taxes | Avg Tax per $1k Sale Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1940 | $671,295 | $6,396 | $9.33 |

| 1940–1959 | $607,466 | $5,766 | $9.53 |

| 1960–1979 | $640,000 | $5,783 | $9.16 |

| 1980–1999 | $714,535 | $7,367 | $10.31 |

| 2000–2019 | $761,061 | $7,685 | $10.10 |

| 2020+ (non-new construction) | $924,420 | $8,016 | $9.12 |

| Grand Total (excluding new construction) | $688,838 | $6,665 | $9.68 |

Several patterns stand out:

- Absolute tax burden increases with newer construction: pre-1980 homes average $5,766–$6,396 in annual taxes, while 2000–2019 properties average $7,685 and 2020+ non-new construction reaches $8,016.

- Effective burden consistency: The Tax per $1k column remains remarkably stable at ~$9–$10 across all eras. This indicates the market prices properties assuming a similar overall tax load, regardless of age.

- Pre-1940 premium: Outside recent construction, pre-1940 homes command the highest average sale prices ($671,295) despite paying among the lowest absolute taxes.

Photo: Portland Appraisal Blog (CC BY-SA 4.0)

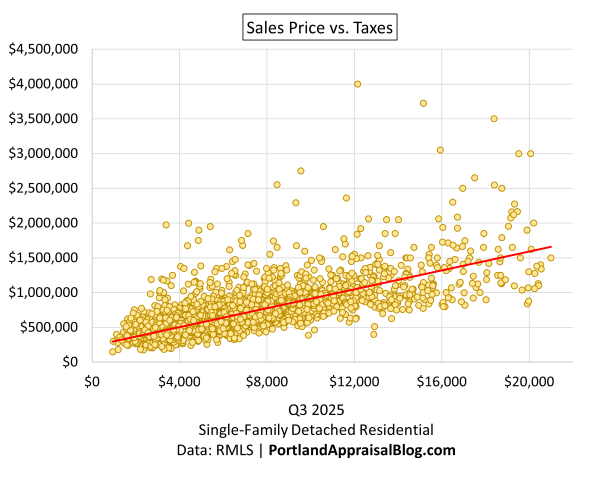

Note: Scatter plots are limited to properties with annual taxes of $21,000 or less to highlight the primary distribution and improve readability.

This scatter shows a strong positive correlation, confirming the market efficiently incorporates expected tax burden into pricing.

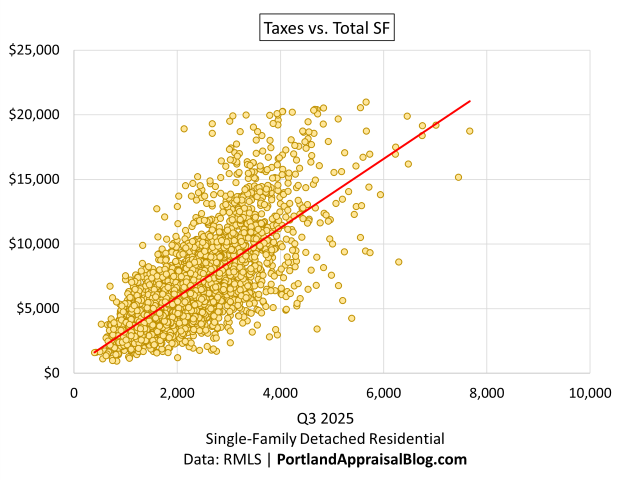

Note: Scatter plots are limited to properties with annual taxes of $21,000 or less to highlight the primary distribution and improve readability.

Here, numerous low-tax outliers are visible below the trend line—properties paying substantially less than size and location would otherwise suggest, consistent with Measure 50 compression.

Taken together, the data reveals a market that rewards older stock with lower absolute taxes without discounting sale prices accordingly. When a MAV reset occurs, absolute taxes move toward levels seen in newer comparable properties, creating the potential for noticeable increases in annual carrying costs.

In the following sections, we explore the specific veteran and active-duty exemptions and the 2024 guidance change that can trigger this alignment.

The Veteran and Active-Duty Exemptions

The exemptions at the center of the current concern are partial property tax reductions for certain military veterans, surviving spouses, and active-duty service members. With approximately 267,000 veterans living in Oregon (and over 114,000 in the Portland metro region), even a fraction of qualifying owners selling or changing status can affect a meaningful number of transactions.

The disabled veteran or surviving spouse exemption (ORS 307.250) provides a reduction to assessed value for homeowners with a service-connected disability rating of 40% or higher (or unremarried surviving spouses). For the 2025–2026 tax year, the reduction is up to $31,565 (service-connected) or $26,303 (standard), worth roughly $400–$700 in annual tax savings in Portland metro areas depending on local rates.

A separate active-duty exemption (ORS 307.286) offers a larger reduction (up to $108,366 for 2025–2026) for Oregon-domiciled service members on qualifying active duty outside the state.

Both are partial exemptions applied to the assessed value of the owner’s primary residence and tied to personal status. Eligibility generally requires a one-time application and VA certification (re-filing needed only if moving to a new property or certified by a private physician rather than the VA).

While the direct savings from these exemptions is modest ($400–$700/year for most veteran claims), the 2024 DOR guidance change treats their disqualification as triggering a full MAV reset—potentially closing decades of Measure 50 compression and leading to significantly higher taxes.

Active-duty cases (e.g., exemption ending upon return home) are less common and typically involve properties with less historical compression.

In the next section, we detail the 2024 guidance change and how it activates the reset.

The 2024 Rule Change

For decades, when a veteran or active-duty partial exemption ended, county assessors typically removed the reduction but preserved the underlying compressed MAV, allowing it to continue growing at the standard 3% rate.

This practice changed with updated guidance from the Oregon Department of Revenue, effective for disqualifications on or after January 1, 2024.

The DOR clarified that disqualification from a partial exemption triggers the constitutional requirement to recalculate MAV using the Changed Property Ratio (CPR)—the county-wide ratio of average MAV to average RMV for the property class. The new MAV becomes current RMV multiplied by the CPR (typically around 0.54 for residential properties in Portland Region counties for the 2025–2026 tax year).

This administrative enforcement of the existing constitutional language means the modest exemption savings ($400–$700/year) is no longer the only consequence. The reset can close much of the Measure 50 compression gap.

In the Portland Region data, pre-1980 homes average $5,766–$6,396 in taxes. A reset aligns absolute taxes closer to 2000+ levels ($7,685–$8,016 average), producing increases commonly in the $1,500–$4,000 annual range on typical sales, with $4,000+ possible in deeper-compression or higher-rate scenarios.

The change is statewide, though impacts vary by local appreciation and rates. Some counties have noted the potential for “significant increase” on loss of exemption.

In the next section, we examine the real-world implications for transactions and what appraisers should watch for.

Real-World Implications

The 2024 guidance change does not turn every pre-1997 home sale into a crisis, but it introduces friction that can affect negotiations, marketability, and reconciliation of comparables.

Typical tax increases fall in the $1,500–$4,000 annual range for properties in the Portland Region dataset ($600,000–$800,000 sale prices with pre-1980 build years). This translates to $125–$333 extra per month.

The Silent Car Payment

In late 2025 terms:

- Average used-car payment: ~$532/month

- Average new-car lease: ~$596/month

- Average new-car purchase payment: ~$748/month

A $2,000–$4,000 annual increase ($167–$333/month) is less than a typical car payment but still noticeable—equivalent to a permanent, non-negotiable “utility bundle” that never goes away. For buyers already stretched in a higher-interest-rate environment, it can shift affordability and prompt renegotiation.

Outlier cases with deeper compression (often “sweet” pre-1940 homes in high-appreciation locations) can see $4,000–$8,000+ increases ($333–$667/month)—territory overlapping average used-car or new-lease payments. These are the transactions Oregon REALTORS described as producing “increases in the thousands,” sometimes requiring substantial seller concessions or risking fallout during due diligence.

The primary impact is often on marketability rather than outright deal death:

- Savvy buyers (or their agents/lenders) anticipate the higher future taxes and adjust offers downward.

- Sellers—particularly veterans or surviving spouses downsizing—may receive lower net proceeds (capitalizing a $3,000 increase at 6% equates to ~$50,000 less effective value).

- Listings can linger if the low current taxes mask the post-closing reality.

For appraisers, this creates a new lens for outliers:

- A comparable with an unexplained lower price, large concession, or extended days on market may reflect buyer reaction to a pending MAV reset.

- Low-tax outliers in the grid (visible in the Taxes vs. Total SF scatter) could indicate compressed MAV or an active exemption—worth verifying via county records when material.

The change is statewide, but effects are most pronounced in areas with strong historical appreciation, like the Portland Region.

In the next section, we outline practical steps appraisers can take to identify and address this factor in reports.

What Appraisers Should Do

The 2024 guidance change introduces a marketability factor that appraisers in Oregon should consider when the subject or comparables involve pre-1997 properties, particularly those with potential veteran or active-duty exemptions.

Practical Checklist

- Verify Exemption Status Review county tax records and the preliminary title report (if available) for indications of an active veteran, surviving spouse, or active-duty partial exemption. Many counties list it on the property tax statement or online portal.

- Estimate Post-Transfer Tax Liability If an exemption is present and likely to disqualify on transfer (e.g., sale to non-qualifying buyer), note the potential increase. Use county assessor tools or CPR data to project the reset MAV (current RMV × CPR) and resulting taxes. Typical jumps in the Portland Region fall in the $1,500–$4,000 annual range, with higher amounts possible in deep-compression cases. Note that tax rates vary by code area.

- Comment on Marketability When Material Include commentary if the differential is significant: “The subject property currently benefits from a veteran partial exemption expected to end upon transfer, potentially increasing annual taxes by an estimated $X. This may affect buyer affordability and market reaction.”

- Reconcile Outliers with This Lens Low-tax outliers in the sales grid (visible in Taxes vs. Total SF analysis) may reflect compressed MAV or an active exemption—a “decaying asset” under the new guidance. Check effective tax rate (annual taxes ÷ sale price): ~0.6–0.8% may indicate compression; consider post-reset alignment (~1.1–1.3%) in reconciliation. Using a compressed comparable without adjustment risks overvaluing the subject’s marketability, as savvy buyers increasingly factor in the reset.

- Use Dual Scenarios if Appropriate For subjects with active exemptions, provide current and projected post-reset tax estimates in the addendum or comments to inform the intended user.

Resources:

- County assessor websites (tax statements often flag exemptions)

- DOR Veteran Exemptions page

- MAV Manual for general mechanics

As resets propagate into closed sales (expected more visibly in 2026 onward), this factor may explain otherwise puzzling comparables. Early identification helps ensure accurate valuation and informed clients.

In the closing section, we look at the broader outlook.

Closing Thoughts

The 2024 DOR guidance change is an administrative enforcement of a long-standing constitutional provision, but its impact is only now becoming visible as disqualifications occur and 2025–2026 tax statements arrive. Larger effects are expected in the 2026–2027 cycle as more veteran-owned properties sell or change status.

The 2025 Oregon Legislative Session saw bills (e.g., HB 2361/SB 387 aiming to lower the disability threshold, HB 3287 to increase exemption amounts) intended to expand veteran benefits. While these efforts highlight recognition of the issue, none addressed the MAV reset trigger itself. The constitutional requirement remains unless amended or re-interpreted.

For appraisers working in the Portland Region and similar appreciation-driven markets, this issue adds one more layer to marketability analysis. Low-tax outliers in older properties represent a benefit that can evaporate on transfer—reliable today, but potentially “decaying” tomorrow.

Awareness helps everyone involved: appraisers reconcile comparables more accurately, agents counsel clients proactively, and buyers/sellers avoid surprises.

If you encounter real-world examples (anonymized comps with concessions due to reset concerns, or listings noting the risk), please share them for future updates. Documenting patterns strengthens our collective understanding.

Thank you for reading this Appraisal Deep Dive. Stay informed and precise in your work.

Quick Reference Cheat Sheet

| Reset Formula | Real Market Value (RMV) × Changed Property Ratio (CPR) |

|---|---|

| Typical CPR (2025–2026, Portland Region residential) | ~0.54 (updated annually each October) |

| Reset Trigger | Disqualification from veteran/active-duty exemption |

| Typical Annual Increase | $1,500–$4,000 ($125–$333/month) |

| Outlier Increase | $4,000–$8,000+ ($333–$667+/month) |

Sources & Further Reading

- Forms Tip of the Week: Oregon REALTORS

- ORS: Chapter 307

- Oregon DOR: Notice Filing Tracked Changes

- Oregon DOR: Maximum Assessed Value Manual

- Oregon DOR: Disabled Veteran or Surviving Spouse Property Tax Exemption

- Oregon DOR: Property Tax Exemptions

- Oregon DOR: 2025-2027 Tax Expenditure Report

- Oregon Department of Veteran Affairs: Benefits & Programs

- Estimate of Number of Veterans in Oregon: ODVA

- Estimate of Number of Veterans in Portland Region: Axios

- Oregon Constitution: 2024 Edition

- Clackamas County: Veteran’s Tax Exemptions

- Multnomah County: Disabled Veteran Exemption

- Multnomah County: Veteran’s Surviving Spouse Exemption

- Multnomah County: Active Duty Military Exemption

- Multnomah County: Changed Property Ratios (2025-2026)

- Washington County: Veteran’s Property Tax Exemption

- Washington County: Changed Property Ratios (2025-2026)

- Douglas County: Acknowledgement of Potential Increase

- Average Car Payment 2025: LendingTree

- The Portland Region Q3 2025 Market Update: Portland Appraisal Blog

Thanks for reading—I hope you found a useful insight or an unexpected nugget along the way. If you enjoyed the post, please consider subscribing for future updates.

CODA

Are you an agent in Portland who wonders why appraisers always do “x”?

A homeowner with questions about appraiser methodology?

If so, feel free to reach out—I enjoy connecting with market participants across Portland and the surrounding counties, and am always happy to help where I can.

And if you’re in need of appraisal services in Portland or anywhere in the Portland Region, we’d be glad to assist.